Sam Bonnifield was born in August 1845 in Ohio. He was perhaps a sea captain on the Steamer Humboldt and came to Alaska as early as 1888.

Sam Bonnifield was a professional gambler and saloon owner who followed the gold from Skagway to Dawson City to Fairbanks in the early 1900’s. It is said he won the Yukonia Hotel and then lost it in one night. He and his brother moved to Fairbanks and opened the First National Bank, which shipped out $3 million in gold dust before the depression hit. Bonnifield was known as “Square Sam” and “Silent Sam” because he treated people fairly. He took the near failure of his bank very hard. He became despondent and suffered a “nervous breakdown”, kneeling in the snow in front of his bank crying, ”O God! Please show me the way out.”

In August 1910, the Fairbanks Daily News Miner noted that Sam Bonnifield arrived in town after walking the Valdez Trail. He spent a year recovering on the family farm in Kansas. The newspaper celebrated his return by saying, “No man ever lived in the North who has more real friends than has Sam Bonnifield, and the entire community will be glad to have him here once again.” In October 1911, the Alaska Citizen ran the headline “Sam Bonnifield is Insane Once More.”

“Sam Bonnifield was taken into custody by the Marshall’s office on Wednesday last on the charge of insanity, and placed in the federal jail. He has been unbalanced for some time, but his condition only became very noticeable the day of his arrest.

Bonnifield has never entirely recovered from the mental breakdown occasioned three or four years ago when the First National Bank, of which he was president, went on a script basis. He was taken Outside for treatment at the time of his breakdown and later walked into Fairbanks over the trail.

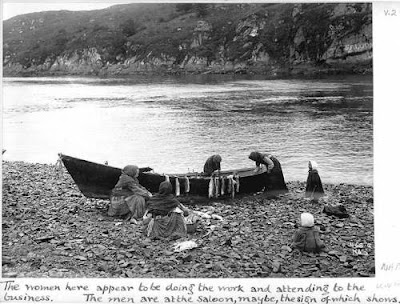

A few days before his arrest he drew quite a sum of money from the bank and distributed a part of it among the laborers around town; the balance he carried across the river and played with it in the sand.

When arrested he violently talked about President Taft, Cardinal Gibbon and other of prominence, saying that money is their god.”

Sam Bonnifield was found to be “insane” by a jury of six men and taken to Portland. He was admitted to Morningside Hospital on December 23, 1911, where he stayed until June 26, 1914. A few months after his discharge, he received a letter from Dr. Henry Waldo Coe, the head of Morningside Hospital, verifying that he was “recovered”. Dr. Coe went on to give him the following advice:

“All that I can ask of you is that you do not take life too earnestly or strenuously. As I understand it, you are not compelled to do two men’s work. You have worked hard and are entitled to an easier time. Take an easy time.”

Not much is known about Sam’s life after his stay at Morningside. He died in 1943 in Seattle from being hit by an automobile.

1900; P. Berton p 121, 423; The Mysterious North; Gates p124; Morningside Hospital website.