On this famous date of the Titanic disaster, here is a local marine disaster. I first saw a number of deaths on the 4th of July 1914 and for years tried to find out about what happened. You will not find this story anywhere else.

On the evening of July 3, 1914 a few young guys in Skagway decided that they did not want to spend the holiday in town, but instead go to the big city, Juneau. So they piled in the little gas-powered boat “Superb” piloted by Captain George Black. On the 3rd of July at 9 p.m it was still light, and would be for another two hours. As they sped away from the dock, these 20 men waved goodbye to their friends as a light wind from the south picked up. By the time they passed Haines and got to Seduction Point, they were making little headway in the fierce south wind. Capt. Black decided to turn around and head for Haines where they pulled in about 1 am. There, 4 passengers off-loaded and 4 other passengers, including Myrtle Burlington, an African-American woman known as the “Smoked Swede” got onboard. At 2 am they decided to push on to Skagway, only 12 miles away. Capt. Black crossed Lynn Canal and tried to stay close to the east side. When they got to about a half mile south of Sturgill’s wood mill, the boat lurched throwing the passengers to the port side. Now the boat flipped over throwing everyone into the dark water. This was at 4 am and dawn was just beginning, but they were in the shadow of the mountains. Three men who were sleeping below were barely able to get out, Mr. Orchard broke a window to get out, badly cutting his hand.

The shock of the cold water must have been bitter, but once their clothes became waterlogged it was all they could do to cling onto the sides of the overturned boat as it drifted out away from shore. By now, Jud Matthews tried to save the Austrian, Amerena and Myrtle by tearing off her clothes and hooking her arm onto the boat. Tom Running finally decided to swim to shore and once he reached Sturgill’s, he ran back through the woods, losing the trail, to town where he got Charles Rapuzzi and Wirt Aden as well as Tom Ryan who headed out in boats. It was now 6:30 am. When they reached the boat which was now clearly seen from shore, the only survivors were Arthur Boone, Sam Radovitch, Orchard, Cassie Kossuth (see earlier blog), Jud Matthews, Peterson, and George Black. Rescuers recovered the body of John Logan and searched for the other 11 all day, cancelling the town’s festivities.

Lost were: Stanley Dillon, age 18, Henry Bernhofer, age 27, John Eustace Bell, Oscar Carlson, Bob Saunders, Lynch, Sam Rodas, Myrtle Burlington, Thomas Mateurin, Monte Price and Nicholas Amerena.

Later that day when it was realized the bodies had sunk to the depths of the ocean, the search was called off. Because so many people had come to town for the baseball games and the dance it was decided to go ahead with those events.

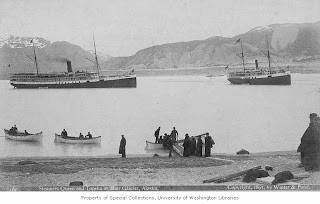

A few days later there was an editorial questioning why there was not an inquest into the accident, but it would seem there was none. Seen above is the scene of the accident, on a calm day.

from the Skagway Alaskan of July 5, 1914.