The sternwheeler Columbian was lost in the worst accident in the Yukon River’s history on September 25, 1906. On the day of the accident, The Columbian was carrying only one passenger—Ernest Winstanley, a stowaway who had sneaked aboard, pretending to be the caretaker of the cattle on board. One report said he was kicked off when the ship docked at Tantalus, but another gave his medical condition while in hospital in Whitehorse.

The explosion happened at Eagle Rock when Phillip Murray showed a loaded gun to Edward Morgan, who accidentally discharged the gun into the load of blasting powder stored on deck. Morgan was killed instantly. Following the ensuing explosion and fire, the captain grounded the ship on shore and those uninjured or killed by the blast jumped ashore.

The explosion blew out the sides of the vessel, scattered men and cargo in the water, and in less than five minutes had involved the whole inside of the ship in a mass of seething flame.

The crew had no provisions and no way to easily go for help. The closest telegraph office was thirty miles away at Tantalus. A party of three set out on foot but they were overtaken by Captain Williams and Engineer Mavis in a canoe they had borrowed from a woodcutter.

Arriving at Tantalus after midnight, they woke up the telegraph operator who sent out a message about the disaster with no response—all the other operators were asleep. The first to receive the message, at 9:00 a.m. on September 26, was at Whitehorse. The first ship to arrive at the scene of the explosion was the sternwheeler Victorian, arriving at 7:00 p.m. Captain Williams had returned that morning to find that Carl Christianson and John Woods had died during the night. Phillip Murray died shortly after being carried aboard the Victorian.

Another sternwheeler, the Dawson, had been dispatched from Whitehorse with a doctor and nurses aboard. The Dawson had not received the news until 1:00 p.m. on September 26 and at 1:00 a.m. on September 27, the Dawson took the crew of the Columbian on board and returned to Whitehorse. Soon after, when Lionel Cadogan Cowper, the purser died in Whitehorse the death toll rose to six men.

The Whitehorse Star reported:

“Ernest E. Winstanley, the only survivor among seven victims of the explosion and fire on the steamer Columbian, which disaster occurred on the Yukon river on Tuesday, the 25th of September, is still at the general hospital at this place where, under the skillful treatment of J.P. Cade and careful nursing of the hospital corps, it is believed he will recover.

Winstanley displays wonderful fortitude and it is believed will be able to leave the hospital in another month or six weeks. His father Ernest Winstanley, arrived Sunday from Dawson and is spending much of his time at his son’s bedside.

The bodies of Mate Welsh and Fireman Morgan, who fell or jumped into the river after being horribly burned, have not yet been recovered.”

Then the Weekly Star reported on October 12, 1906:

“Today at 11:30 an artery in Winstanley’s neck burst and this may tend to complicate his chances for recovery.” Apparently they credited his long woolen underwear with keeping him from being burned over much of his body, but his face and hands were burned. He did survive and on September 31, 1906 he moved to Galiano in southern British Columbia where he was a farmer in the 1911 census.

Also lost was her cargo of 150 tons of vegetables and meat, and 21 head of cattle.

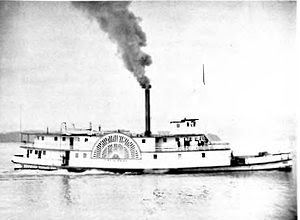

The disaster is described in “Fire on the Yukon” by Sam Holloway. A memorial to the victims was erected in the Whitehorse Cemetery by the employees of the British Yukon Navigation Company. The Columbian is seen above in better days in 1903.

Explore North; NWMP record; wikipedia; Dawson Daily News, September 26, 1906; Hougen group website; BC 1911 census online; Yukon Archives – Benjamin Craig’s list of people leaving the Yukon.